One of the problems that one realizes only in the place itself (in this case, in the Kyrgyz Osh) is the absolute luxury we have at home, in a landscape where the tradition and history of local research has led to the creation of a detailed network of knowledge of material culture. In the Czech Republic we have thick books with a list of findings, thin books with maps of localities by region and on every corner of a local archaeologist who “dates” sherds brought from the excavation of the local gas connection. I am not saying that this is a paradise of archaeological knowledge, but it is possible to lean on at least some foundation and write something meaningful. For example, such an essential thing – wheel-turned pottery, according to our archaeological tradition, appears “sometimes around the Celts”, which is a kind of “fixed point in Universe …”

In Kyrgyzstan, such luxury is not available – empirical material research was last conducted by Soviet archaeologists (who after their engagement took the findings or left them without proper documentation) and the young republic in the nineties had a completely different priority than creating a local typological series of Kypchaks pottery…

Surprisingly, one realizes that he is in a “green field”, a state of research that existed in Bohemia in the mid-19th century.

This epistemological deficit, of course, leads to the search for archaeological analogies beyond the local scene; unknown findings must be “leaned” on something already explored, which can also lead to bizarre results. Something similar to H. Muller-Karpe (indirectly) dates the Lusatian findings in the “Small Nameless Village of East Poland” using several painted sherds from southern Italy.

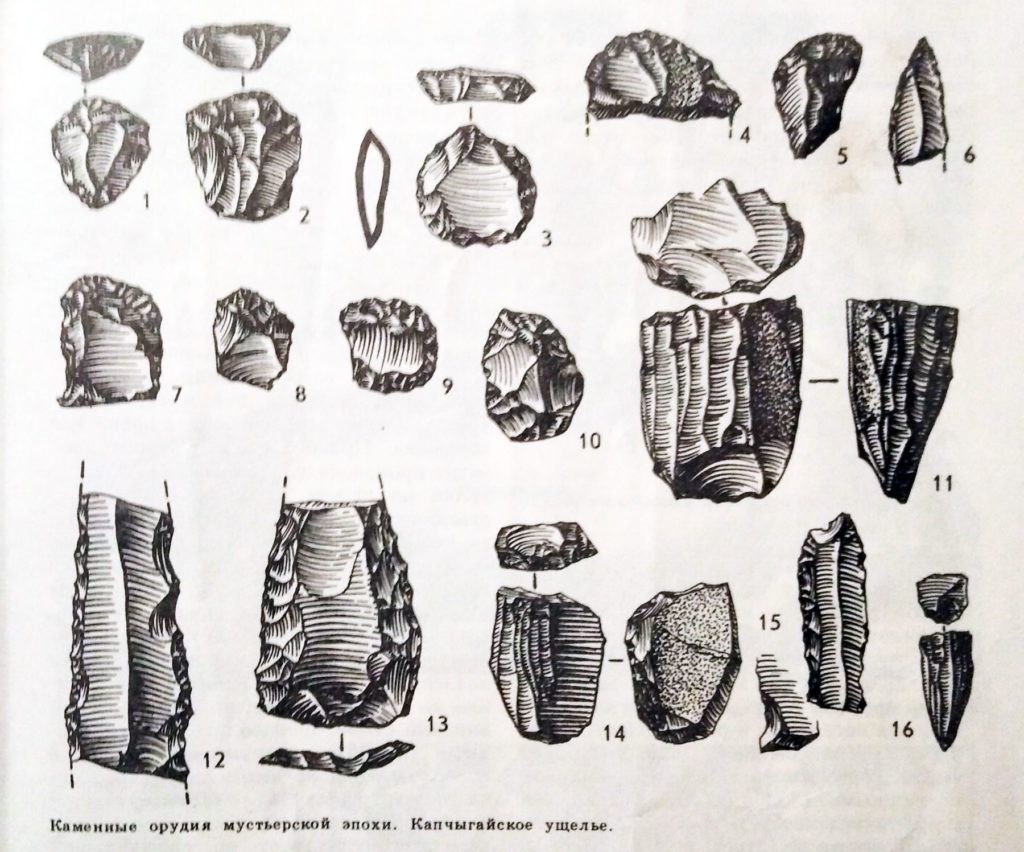

Or, is it possible to label several remnants of korn technology in Central Asia as defined somewhere in Dordogne?

(explanation for those who do not control russian Cyrillic: the clefts in the picture are labeled as Mousterien)